The burden of Fallot’s tetralogy among Nigerian children

Introduction

History of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) dates back to over 300 years. The Danish Anatomist, Niels Stensen, gave the first description of the cardiac malformation in 1672 and Sandifort Edward in 1777 described the symptoms and anatomic findings of TOF in a child (1). However, the defect was named after Étienne-Louis Arthur Fallot in 1888 because it was he who first accurately described the clinical and complete pathologic features of the defects (1,2). The first palliative treatment was performed by the duo of Helen Taussig and Alfred Blalock who created a shunt between the subclavian artery and pulmonary artery called the Blalock-Tausig shunt (2). Subsequently the development of other shunts followed. Since then advances in cardiac surgery has allowed patients with TOF to have corrective surgery and afforded affected patients to live a near normal life.

TOF is comprised of four cardiac abnormalities which are, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO), ventricular septal defects (VSD), overriding aorta and right ventricular hypertrophy. There are other anatomical variants and cardiac anomalies associated with TOF. Some anatomical variants include TOF with pulmonary atresia, absent pulmonary valve, double outlet right ventricle, atrial septal defect or a patent ductus arteriosus (1). In some cases, there may be associated coronary artery abnormalities (1).

The etiology of TOF is multifactorial (3). Chromosomal abnormalities occur in up to 25% of patients with TOF (4). Some of those includes trisomies 13, 18 and 21 and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (1,3,4). Trisomy 21 and 22q11.2 are the most common abnormalities (3). Chromosome 22q11.2 microdeletions have been reported in up to 20% of patients with TOF and pulmonary stenosis and 40% in TOF with pulmonary atresia (1,4,5). Other less common genetic anomalies have also been documented (6,7). Risk of recurrence in a family is approximately 3% (1). Association with maternal rubella and other viral infections, first-trimester intake of retinoic acid, untreated phenylketonuria and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus in pregnancy have been documented (2,8).

Onset and severity of symptoms depends on the degree of RVOTO (1,9). In mild RVOTO, the neonate may be asymptomatic and acyanosed. A systolic murmur may be the only finding in such cases consequent upon the turbulence through the right outflow tract (10). However with more severe obstruction, patients may present in the neonatal period with marked cyanosis that may require intervention. As the infant grows older, symptoms and signs become more apparent as they outgrow their pulmonary blood supplies. Cyanosis, respiratory distress and hypercyanotic (TET) spells occurs. The TET spells are a life-threatening clinical condition that may be fatal. It results from spasm of the right outflow tract with increased right to light shunting of deoxygenated blood through the VSD. Precipitating factors include activities such as feeding, crying, exertion or it may occur without warning (11).

Diagnosis of TOF is confirmed using echocardiography (1). TOF can be managed medically and surgically. The decision of the mode of management depends on the degree and type of RVOTO and the center’s protocol (1). Patient with critical pulmonary stenosis may require prostaglandin infusion to maintain the patency of the ductus arteriosus to increase pulmonary blood (1). Patients with such severe right ventricular outflow may require early surgical intervention. A complete repair may also be done immediately (12). In settings where palliative procedure cannot be offered or when diagnosis was missed, patient may present with TET spell which is managed medically.

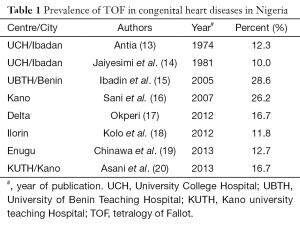

TOF constitutes 10–26.2% of all congenital heart disease in Nigeria (13-20). This is from reports on surveys of prevalence of congenital heart disease in the country. There are only very few reports on TOF in Africa especially from sub-Saharan Africa. At best TOF is only mentioned as part of reports of surveys of other congenital heart disease or as case reports in the region. These reports contain only very few cases of TOF over a short period of time. There has been no report on cohorts of children with TOF in West Africa. This article will describe the pattern and presentation of children diagnosed with TOF patients in a tertiary hospital in sub-Saharan Africa over a 9-year period. This is to make data available on these group of subjects for reference purpose for future research in the region, create awareness on TOF among health professionals in the region and for advocacy on the urgent need to establish Pediatric Cardiac centers in Nigeria so that these children can be salvaged, especially the need for collaboration with established Pediatric Cardiac centers in the developed countries in order to improve the outcome of children born with TOF in the West Africa region through early diagnosis and prompt intervention.

Methods

Data of all cases of TOF diagnosed with echocardiography at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH), between January 2007 and December 2015 were collected prospectively. The center is a tertiary hospital in South Western Nigeria. The Hospital receives referral from the South Western region.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of LASUTH. Children with suspected cardiac lesions are referred to the department of Pediatrics for evaluation. History and physical examination including measuring of their oxygen saturation with oximeter were done on all the children. Chest radiograph, electrocardiography, echocardiography and other ancillary investigations are carried out as required.

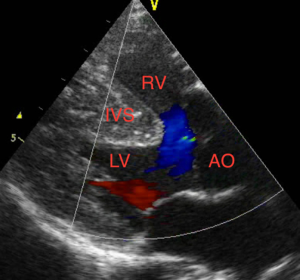

All the subjects referred for evaluation were reviewed clinically before investigation. A 2-D echocardiography machine with facility for colored Doppler and M-mode is available. It is a GE Vivid Q echocardiography machine with reference number 14502 WP SN 2084 and diagnosis of TOF was made with echocardiography (1). All the patients were followed up at the pediatric cardiology clinic. Both palliative and definitive surgical correction was required by all the subjects but this is not always available in Nigeria. Cardiac surgery for congenital heart diseases in Nigeria before now has not been available on a regular basis, it was only available when mission group visits, the visit last for only few days with only few cases done, there also exists challenges of availability of diagnostic facilities such as cardiac catheterization until recently, lack of availability of support staff and other lifesaving consumables and blood products made performing surgery on children with TOF almost impossible hence the patients were referred outside Nigeria for surgery (21). The patients who had surgical correction outside Nigeria were referred back to the unit after the correction and they were followed up in the unit.

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. The subjects’ age, sex, indication for echocardiography, echocardiographic findings and outcome and were documented. The prevalence of TOF was calculated. Tables and charts were used to depict those variables. Descriptive statistic is presented as percentages or means and standard deviation. Means of normally distributed variables were compared using the Students’ t-test and proportions using Chi-square test. Skewed distributions were analyzed using appropriate non-parametric tests. Level of significance set at P<0.05.

Results

A total of 165 patients with echo diagnosis of TOF were documented between January 2007 and December 2015. A total of 326,662 children ≤13 years of age were seen at the Department during the study period. The prevalence of TOF amongst the children who were seen in the hospital during the study period was 5.1 per 10,000 children. A total of 1,693 echocardiography were done and 1,123 had congenital heart disease. Of the 1,123 patients with congenital heart disease, 351 had cyanotic congenital heart disease. TOF accounted for 14.7% and 47% of congenital heart disease and cyanotic congenital heart disease respectively. Table 1 shows the prevalence of TOF in the study subjects in other centers in Nigeria while Figure 1 is a representative echocardiographic image of a patient.

Full table

Clinical presentation of the subjects

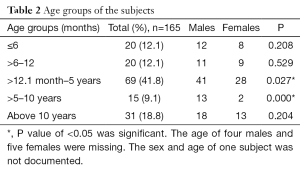

There were 99 males and 65 females with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. The sex of one patient was not documented. The distribution of the age at diagnosis was skewed to the right with an age range of 2 days to 13 years and median age of 36 months. The median ages for both sexes were 45 and 36 months respectively. There was no significant difference in the mean age at diagnosis of both sexes (P=0.147). Most of the patients, 41.8%, were between 1–5 years of age at diagnosis. There were more males diagnosed in the sub-groups of 12 months to 5 years (5) and those between 5 and 10 years compared with the females, P=0.027 and P<0.001 respectively as shown in Table 2.

Full table

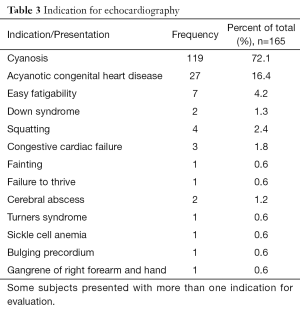

The most common indication for cardiac evaluation in the study subjects was cyanosis with a suspicion of a cyanotic congenital heart disease. One hundred and nineteen (72.1%) children were clinically cyanosed on presentation. Some other indications for cardiac evaluation included clinical suspicion of an acyanotic congenital heart disease, Down syndrome and Turners syndrome. Some patients had more than one indication for cardiac evaluation. Two of the patients presented with cerebral abscess while one presented with gangrene of the right forearm and hand. Table 3 depicts the indication for cardiac evaluation.

Full table

Discussion

Different researchers in Nigeria have published varying rates depending on the geographical region. In the present study, TOF was recorded in 14.7% of all congenital heart diseases. Previous studies in Nigeria have documented rates between 10% and 26.2% of all congenital heart diseases (13-20). Jaiyesimi et al. (14) in the 1981 recorded the lowest rate of 10% in South Western Nigeria while Ibadin et al. (15) in South Southern Nigeria had the highest rate of 28.6%. We recorded a rate almost similar with that by Asani et al. (20) (16.7%) in a tertiary hospital in Northern Nigeria, and Okperi (16.7%) (17) in South Southern Nigeria.

The various studies in Nigeria differ in methodology, age range of the study subjects, duration and number of patients reviewed. This, in addition to regional variation may account for the varying figures documented. Earlier studies by Antia (13) and Jaiyesimi et al. (14) at University College Hospital Ibadan, were both prospective and were conducted over 5 and 10 years respectively and both studies had different prevalence rate for TOF, 12.3% and 10% respectively despite both been conducted in the same center. However, both studies were conducted at different times and had different number of subjects reviewed. Ibadin et al. (15) and Okperi (17), both in South Western Nigeria, also had varying prevalence of TOF. Both were prospective studies, however, the former was over a 9-year period and had a total of only 49 cases of CHD during the study period while the later was over a 2-year period and reviewed only 18 subjects with CHD. Sani et al. (16) and Asani et al. (20) both in the same region, and institution had different prevalence of TOF, 26.2% and 16.7% respectively. Sani and colleagues (16) conducted a retrospective review of cases of congenital heart disease in two study centers within the same locality over a 2-year period and recorded 122 cases of CHD. They had a larger number of cases of TOF compared to Asani et al. (20) probably because one of the centers used for the study was a cardiac referral center in the region where echocardiography was done and, in addition, their study subjects comprised children and adults. In contrast, the study by Asani et al. (20) was also retrospective but it was conducted over a 2-year period in one study center and the study subjects were all children.

There was a male predominance of TOF in the present study with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. The finding in this regard is similar with reports from other studies (9,22-26). The underlying cause of this male predominance in TOF is largely unknown. Concerning the clinical presentation of the patients, over seventy percent of the patients in the present study were cyanosed at presentation. This was not surprising given that TOF is a cyanotic congenital heart defect.

The mean age of the subjects at presentation was 50.9±45.9 in months (4.2±3.8 in years). This mean age is almost similar to that reported by Kennedy et al. (27) in Malawi. This is late considering that diagnosis of TOF is made in-utero in developed countries. The finding in the study further confirms the fact that diagnosis of TOF and other congenital heart diseases are usually made between 1–5 years of age in resource-poor countries (20,24,28,29). Late diagnosis of TOF and other CHD in resource-poor countries is due to late presentation, difficulty in assessing specialized care, poverty and poor health seeking behavior (22,23,28,30). The late presentation in this patient is worrisome considering that cyanosis was the commonest indication for echocardiography in these patients; could it be that the parent were not able to recognize bluish discoloration of the lips and tongue (central cyanosis) in these children as abnormal? Unfortunately, the current study did not set out to access the awareness of the parent and caregivers on TOF but a recent study in the current study center, by one of the current authors indicated poor level of awareness of congenital heart disease among the caregivers (30). Does this poor level of awareness also occur among health professionals? Since one could speculate that some of these patients were expected to have been at a healthcare facility at one point or the other; even if for immunization or other unrelated complaints. However, the answers to these questions are beyond the scope of this study. There is therefore an urgent need to increase the awareness of parents and caregivers on congenital heart disease, there is also a more urgent need to evaluate the awareness of health professionals in Nigeria on congenital heart disease including TOF since these healthcare professionals are in a better position to educate the parents and caregivers.

Conclusions

This is the first report on cohort of children with TOF in Nigeria. We report a prevalence of 5.1 per 10,000 children in this hospital base study. The prevalence of TOF in congenital heart disease was 14.7% and this was similar to other studies within Nigeria and the sub-region. Hence TOF is prevalent among Nigerian children. There was a male predominance and most children presented within 1–5 years of age. Cyanosis was the commonest presenting feature and indication for evaluation. Most of the subjects presented late hence were diagnosed after 1 year of age. There is a need to increase awareness of TOF in Nigeria to encourage early diagnosis and hence better outcomes in these subjects.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all the subjects who participated in this study. Caregivers and parents of the subjects including all the healthcare workers who participated in their care are also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of LASUTH and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Bailliard F, Anderson RH. Tetralogy of Fallot. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2009;4:2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhmji S. Tetralogy of Fallot. Medscape article. Available online: . Accessed 25th April 2015.http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2035949-overview

- Villafañe J, Feinstein JA, Jenkins KJ, et al. Hot topics in tetralogy of Fallot. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:2155-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis S. Tetralogy of Fallot with and without pulmonary atresia. In: Nicholas DG, Ungerleider RM, Spevall PJ, editors. Critical Heart Disease in infants and children. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, 2006:755-66.

- Maeda J, Yamagishi H, Matsuoka R, et al. Frequent association of 22q11.2 deletion with tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Med Genet 2000;92:269-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glaeser C, Kotzot D, Caliebe A, et al. Gene symbol: JAG1. Disease: tetralogy of Fallot. Hum Genet 2006;119:674. [PubMed]

- De Luca A, Sarkozy A, Ferese R, et al. New mutations in ZFPM2/FOG2 gene in tetralogy of Fallot and double outlet right ventricle. Clin Genet 2011;80:184-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siwik ES, Patel CR, Zahka KG, et al. Tetralogy of Fallot. In: Allen HD, Gutgesell HP, Clark EB, et al. editors. Moss and Adams' Heart disease in infants, children and adolescents. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:880-902.

- O'Brien P, Marshall AC. Cardiology patient page. Tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation 2014;130:e26-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silberbach M, Hannon D. Presentation of congenital heart disease in the neonate and young infant. Pediatr Rev 2007;28:123-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernstein D. Cyanotic congenital heart lesion: lesions associated with decreased pulmonary blood flow. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BM, St. Geme J, et al. editors. Nelson textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

- Bhmji S. Tetralogy of Fallot. Medscape article. Available online: , accessed 25th April 2015.http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2035949-treatment

- Antia AU. Congenital heart disease in Nigeria. Clinical and necropsy study of 260 cases. Arch Dis Child 1974;49:36-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaiyesimi F, Antia AU. Congenital heart disease in Nigeria: a ten-year experience at UCH, Ibadan. Ann Trop Paediatr 1981;1:77-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibadin MO, Sadoh WE, Osarogiagbon W. Congenital heart disease at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics 2005;32:29-32.

- Sani MU, Mukhtar-Yola M, Karaye KM. Spectrum of congenital heart disease in a tropical environment: an echocardiography study. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:665-9. [PubMed]

- Okperi BO. Pattern of congenital heart disease in Delta State University Teaching Hospital, Oghara, Nigeria. Continental J Tropical Medicine 2012;6:48-50.

- Kolo PM, Adeoye PO, Omotosho AB, et al. Pattern of congenital heart disease in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2012;19:230-4. [PubMed]

- Chinawa JM, Eze JC, Obi I, et al. Synopsis of congenital cardiac disease among children attending University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Ituku Ozalla, Enugu. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:475. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asani M, Aliyu I, Kabir H. Profile of congenital heart defects among children at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital Kano, Nigeria. Journal of Medicine in the Tropics 2013;15:131-34. [Crossref]

- Falase B, Sanusi M, Majekodunmi A, et al. Open heart surgery in Nigeria; a work in progress. J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;8:6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poon LC, Huggon IC, Zidere V, et al. Tetralogy of Fallot in the fetus in the current era. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;29:625-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khadim J, Issa S. Spectrum of congenital heart disease in Basra: an echocardiography study. The Medical Journal of Basra University 2009;27:15-8.

- Kapoor R, Gupta S. Prevalence of congenital heart disease, Kanpur, India. Indian Pediatr 2008;45:309-11. [PubMed]

- Wanni KA, Shahzad N, Ashraf M, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of congenital heart disease in children. Heart India 2014;2:76-9. [Crossref]

- Al Rashed AA, Al Jarallah AS, Al Hadlaq SM, et al. Congenital heart diseases of children admitted in a university hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Saudi Heart Association 2002;14:86-92.

- Kennedy N, Miller P. The spectrum of paediatric cardiac disease presenting to an outpatient clinic in Malawi. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chew C, Halliday JL, Riley MM, et al. Population-based study of antenatal detection of congenital heart disease by ultrasound examination. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;29:619-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chinawa JM, Obu HA, Eke CB, et al. Pattern and clinical profile of children with complex cardiac anomaly at University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2013;16:462-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Animasahun A, Kehinde O, Falase O, et al. Caregivers of Children with Congenital Heart Disease: Does Socioeconomic Class Have Any Effect on Their Perceptions? Congenit Heart Dis 2015;10:248-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]