Noncardiac thoracic surgery in Abidjan, from 1977 to 2015

Introduction

Activities related to noncardiac thoracic surgery began in 1977 in Abidjan at the Cardiology Institute (Institut de Cardiologie d’Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire) along with the first open heart operation under the guidance of professors Dominique Métras, Andre Ouezzin-Coulibaly and Alexandre Ouattara Kouame (Figure 1). At the beginning, pulmonary resections for pulmonary sequelae of tuberculosis were predominant activities. But to date the operations are more varied with a share of increasing importance given to the surgical management of thoracic trauma.

In this paper, the authors reviewed the activities of noncardiac thoracic surgery since the beginning and analyzed the results.

Methods

This was a retrospective and descriptive study concerning 39 years from 1977 to 2015. This study period was divided into three periods of 13 years each: P1 from 1977 to 1989, P2 from 1990 to 2002 and P3 from 2003 to 2015. Medical records of 2014 operated patients were analyzed: 414 patients in P1, 464 patients in P2, 1,136 patients in P3. The records destroyed in a fire in 1997 were not included in the study. The age, sex, pathologies, types of operations, post-operative complications and mortality were analyzed. Distributions of the main groups of pathologies were compared on the three periods using the fitting χ2. The percentages of death of patients in each of the disease groups, as well as for all pathologies were compared on the three periods using the test for the compliance of χ2. The level of significance of statistical tests was set at 0.05.

Results

Age and sex

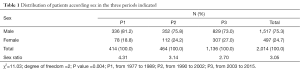

The average age was 35 years in P1 (range 11 months to 71 years), 36.2 years in P2 (range 1 year to 71 years) and 31.6 years in P3 (range 1 month to 78 years). Men predominated in all periods. However the distribution of patients by sex varied significantly over the three periods; In particular, we noted an increase in the proportion of women, resulting in a decrease in the sex ratio (Table 1).

Full table

Pathologies observed

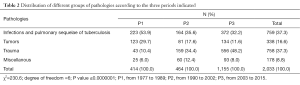

Distribution of important groups of pathologies observed varied significantly over the three periods; in particular, we noted an increase in trauma cases (tripling between P1 and P2, 140% between P2 and P3), and a decrease in tumors percentages, and infections and pulmonary sequelae of tuberculosis (Table 2).

Full table

Infections and pulmonary sequelae of tuberculosis

Pathologies such as symptomatic bronchiectasis, aspergilloma, “destroyed lungs” secondarily developed on pulmonary sequelae of treated and cured tuberculosis dominated pathologies over the periods. But non tuberculous empyema occupied the first place in the last period (Table 3).

Full table

Tumors

The distribution of major types of tumors varied significantly over the three periods. In particular, we noted a tripling of the proportion of mediastinal tumors between P1 and P2 followed by a stagnation between P2 and P3, an increase chest wall and pleural tumors between P2 and P3, and a decrease lung tumors between P1 and P3 (Table 4). However the primary or secondary malignant tumors were predominant.

Full table

Chest trauma

The increase in cases was very important over the three periods. The distribution of the three periods of the types of trauma revealed a particular increase in blunt trauma between P2 and P3. The variation was statistically significant. The number of penetrating chest trauma remained higher (Table 5).

Full table

Miscellaneous

They were dominated by the spontaneous pneumothorax cases (Table 6). No case of congenital disease has been reported in the last period.

Full table

Surgical procedures

The surgical management of thoracic trauma is on the increase (56.9% in P3) followed by the pleural surgery (21.3%) and pulmonary resections (13.9%) (Table 7).

Full table

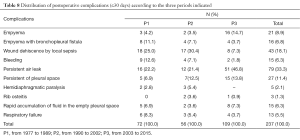

Postoperative complications (≤30 days)

Major postoperative complications

Persistent air leak >7 days was the predominant complication over the three periods. Postoperative empyema increased in P3 (14.7%). While the wound dehiscence by local sepsis was down (3.7% in P3 vs. 30.4% in P2 and 25% in P1) (Table 8).

Full table

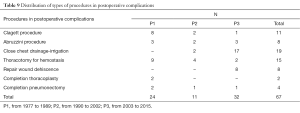

Treatment of major postoperative complications

Close chest drainage-irrigation was the most frequent procedure performed to control a serious infection like postoperative empyema without bronchopleural fistula or after the closure of a bronchopleural fistula (Table 9).

Full table

Mortality

Overall mortality decreases from 5% in P1 to 3.4% in P3. The mortality in the group of tumors was the most important; the highest value being observed in period P3 (P=0.0015). However, this increase was offset by the increase of trauma with low mortality, resulting in a non-significant reduction in mortality across all diseases (Table 10).

Full table

Postoperative stay

The distribution showed an average of 12 days with a maximum of 9 months in P1; 8.5 days with a maximum in 3 months to P2; 8 days with a maximum of 3 months in P3.

Comments

Our relatively low number of patients can be explained by limited access to thoracic surgical care secondary to poverty of the population, the lack of a health insurance system, inefficient medical infrastructure, and the high cost of thoracic surgery (1).

Surgery of pulmonary sequelae of tuberculosis was frequently performed during the initial two periods (P1 and P2), the decrease in the last period (P3) can be explained by wider access to early, free pharmacologic treatment for tuberculous patients. Surgery for chest trauma has increased with military-political crisis since 1999. Violence and firearms use explain our high number of thoracic injuries (2).

Postoperative empyema with or without bronchopleural fistula remains a frequent complication. It frequently occurs after surgery of pulmonary sequelae of tuberculosis (3). It can be minimized by a careful preoperative preparation (4). The treatment of the empyema without bronchopleural fistula by close chest drainage-irrigation procedure (5) is our treatment of choice since 1995. Before, we have performed Clagett procedure (6,7), but because of its highly negative psychological impact on the patient’s family and the difficulties of home care, the Clagett procedure is now reserved for cases of failure of continue close chest drainage-irrigation procedure. Concerning the treatment of the bronchopleural fistula, we perform the procedure initially described by Abruzzini (8) or variations (9,10) through a transmediastinal approach for control of bronchopleural fistula in an aseptic region.

The higher mortality observed in the group of malignant tumors is secondary to presentation in late, advanced stages of disease. In addition to pulmonary tumors, mediastinal tumors are more frequently diagnosed since the advent of computed tomography. Unfortunately, comprehensive oncological care is still limited in our country. Further investment in hospital infrastructure is necessary including establishment of a radiotherapy center.

Conclusions

Noncardiac thoracic surgery operations are still dominated by infections, pulmonary sequelae of tuberculosis, thoracic tumors and thoracic trauma caused by current armed conflicts and terrorist attacks. Access to thoracic surgical care remains difficult for our population with low economic status, and because of the lack of a health insurance system. Therefore consultation is often obtained in very advanced stage of the disease. Nevertheless overall mortality observed in the practice of this surgery is reasonable and can be further improved.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the statistical work provided by Professor Serge Oga.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Demine B, Kendja F, Tanauh Y, et al. Les coûts de la chirurgie thoracique au CHU de Cocody. Rev Pneumol Trop 2005;4:21-3.

- Demine B, Kendja F, Tanauh Y, et al. Morbidité et mortalité en chirurgie thoracique non cardiaque à Abidjan: Une étude comparative et rétrospective sur deux périodes: 1977 à 1989 et 1990 à 2002. J Chir Thorac Cardio-vasc 2006;10:31-6.

- Kendja F, Tanauh Y, Demine B, et al. Les facteurs de morbidité et de mortalité des pneumonectomies. Notre expérience à propos de128 cas. Revue de Pneumologie Tropicale 2005;3:22-5.

- Kendja KF, Tanauh Y, Ehounoud H, et al. La chirurgie des séquelles pulmonaires de la tuberculose. L’expérience ivoirienne: à propos de 217 cas. J chir Th Cardiovasculaire 2005;9:141-4.

- Potier A, de Saint Florent G, Janssen B, et al. About double drainage empyema treatment with bronchial fistula afer pneumonectomy (author’s transl). J Chir (Paris) 1980;117:651-4. [PubMed]

- Clagett OT, Geraci JE. A procedure for the management of postpneumonectomy empyema. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1963;45:141-5. [PubMed]

- Zaheer S, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, et al. Postpneumonectomy empyema: results after the Clagett procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:279-86; discussion 286-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abruzzini P. Surgical treatment of fistulae of the main bronchus after pneumonectomy in tuberculosis (personal technic). Thoraxchirurgie 1963;10:259-64. [PubMed]

- Perelman MI, Ambatjello GP. Transpleural, transsternal and contralateral approach in surgery of bronchial fistulas following pneumonectomy. Thoraxchir Vask Chir 1970;18:45-57. [PubMed]

- de la Riviere AB, Defauw JJ, Knaepen PJ, et al. Transsternal closure of bronchopleural fistula after pneumonectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:954-7; discussion 958-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]