Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy in juvenile mitral stenosis

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), often neglected by media and policy makers, is a major burden in developing countries where it causes most of the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in young people, leading to about 250,000 deaths per year worldwide (1).

Mitral stenosis (MS) is rarely seen in children and adolescents except in developing countries where rheumatic fever is still endemic (2-4), and up to 25% of patients are younger than 20 years of age (5). This disease has been called juvenile mitral stenosis (JMS) (2). Until the mid-1980s, surgical close or open commissurotomy was the only available treatment. In addition to acute risks of mitral valve surgery in children and adolescents, it has an added disadvantage of requirement of reintervention 10 to 15 years later (6). In adults, percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy (PTMC) yielded results similar to open surgical commissurotomy (7,8) and better results than closed commissurotomy (7). Therefore, PTMC is an attractive alternative in particular setting where mitral valve is pliable with minimal calcifications.

Though there are several studies from Nepal on efficacy of PTMC on different subgroup (9-13) of mitral stenosis, there is no study to evaluate its efficacy in juvenile patients. Thus we aim to study the efficacy of PTMC in JMS.

Methods

It was a retrospective, single centre study, performed at Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal. Medical records of all juvenile patients who underwent elective PTMC from July 2013 to June 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. JMS patients with symptomatic MS and MVA less than 1.5 cm2 with favorable mitral valve morphology were included. Patients with moderate mitral regurgitation (MR), having other significant valve lesions requiring surgical treatment, or evidence of left atrial thrombus was excluded. During the study period 681 PTMC were done. JMS compromised of 131 cases which were less than twenty percent of total PTMC done in the study period. Performa was designed to collect patient information which included; age, gender, rhythm, left atrium (LA) size, mitral valve area (MVA) and mean LA pressure before and after PTMC.

The study protocol was approved by institutional review board (IRB) of Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal. Written and Informed consent was taken from patients and patient party before the procedure. All the variables were entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed and presented as means and standard deviations.

Procedure

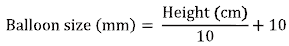

PTMC was done under universal aseptic condition through right femoral venous approach under local anaesthesia. LA mean pressure was recorded before and after the balloon inflation. A simple balloon sizing method, based on the body height, for selection of an appropriate sized balloon catheter was determined using following formula.

Pre and post procedural Echocardiography evaluation: 2 D echo, color flow maping and MVA calculation using planimetry was done before and after PTMC to evaluate MVA, and MR. A trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE) was done one day before the procedure to rule out the presence of LA and left atrial appendage thrombus. On the next day, post procedure MVA and severity of MR was evaluated by transthoracic echocardiograph.

Successful PTMC was defined as increase in MVA >1.5 cm2 with no more than moderate MR. Complications like cardiac tamponade, MR, stroke if present were recorded.

Results

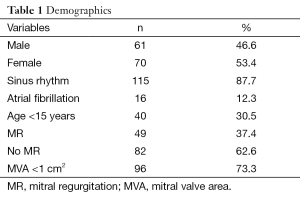

We studied 131 patients of which 70 (53.4%) were female and 61 (46.6%) were male. Forty (30.5%) patients were below the age of 15 years. Patient age ranged from 9 to 20 years with the mean age 16.3±2.9 years. Shortness of breath (NYHA II-IV) was present in all the patients. On electrocardiography (ECG) recordings normal sinus rhythm was present in 115 (87.7%) patients and atrial fibrillation in 16 (12.3%) patients. Left atrial size ranged from 2.9 to 6.1 cm with the mean of 4.5±0.6 cm. Pre procedure MVA of less than 1 cm2 was present in 96 (73.3%) patients; and MVA between 1 to 1.5 cm2 was present in 35 (26.7%) patients. In Pre procedure Echocardiogram Mild MR was present in 33 (25.2%), trace MR in 16 (12.2%) patients, whereas rest 82 (62.6%) didn’t have any MR as shown in Table 1.

Full table

The mean MVA increased from 0.8±0.1 to 1.6±0.2 cm2 following PTMC. Mean LA pressure decreased from their pre-PTMC state of 27.5±8.6 to 14.1±5.8 mmHg. As shown in Table 2.

Full table

Post procedure severe MR was seen in 5 (3.8%) patients. Among them one patient needed MVR after the PTMC, patient died after MVR. Moderate MR developed in 11 (8.4%) patients. Unsuccessful results due to suboptimal MVA 2 was present in 11 (8.4%) patients and post-procedure MR of more than moderate MR in 5 (3.8%) patient. Our success rate was 87.7%.

Complications such as embolic stroke and pericardial effusion were not observed. Three cases underwent the repeat procedure due to inability to cross the mitral valve on first attempt.

Discussion

MS represents a different pattern of rheumatic fever characterized by a “smouldering” sub-clinical course with the majority of the lesions being diagnosed in older patients (fifth to sixth decade) than MR or aortic regurgitation of rheumatic origin (14,15). However, in developing countries, MS progresses more rapidly, presumably due to either a more severe rheumatic injury or repeated episodes of carditis due to streptococcal infections. This results in severe symptomatic MS in the early to mid-teenage and the early twenties which carry a poorer prognosis (16). Patients exhibit severe pulmonary oedema, early severe pulmonary hypertension and eventually severe right ventricular failure (17).

PTMC has become the treatment of choice for symptomatic isolated MS. The immediate results of PTMC are similar to those of close and open surgical mitral commissurotomy. The mean valve area usually doubles (from 1.0 to 2.0 cm2), with a 50% to 60% reduction in transmitral gradient (17). Overall, 80% to 95% of the patients may have a successful procedure, which is defined as mitral valve are a >1.5 cm2 in the absence of complications (17). PTMC also tends to delay the need for MV replacement for about ten years or more and some of these patients may be amenable for redo valvuloplasty (7). Hence PTMC has become the preferred treatment option in symptomatic JMS.

Though there is a female dominance in study by Nagma et al. in patient of all age group (11) (74%) and in elderly patients (10) (77%) at our centre, in this study no significant female predominace was noted in JMS patient. This is similar to a study done among children of less than 15 years of age (52%) done at our centre (9). Our result is similar to the study done in India (18), but there was a female predominance in a study done in Kenya (17).

The success rate of our study was 87.7% which is comparable to other studies done at our centre in different population. Success rate was 94%in children (9), 83.6% in elderly (10), and 100% in pregnant (12).

In another study done by Nagma et al. (11) in all patients of all age group in our centre the success rate was 84%. In this study Successful PTMC was defined as mean LA pressure decrease by >50% as compared to the baseline, MVA increase by >50% as compared to the baseline and final absolute MVA of >1.5 cm2 in the absence of more than moderate MR. Our success rate was better than the study done in India (67.7%) (18). However another study done in another centre of India had a better success rate of 99% with sustained hemodynamic benefits (echocardiographic mean transvalvular gradient and MVA) at 29 months follow up (19). In a study done in Kenya the success rate is (100%) had better success rate than ours (17).

While comparing 40 juvenile patients aged 20 years or younger with 40 adult patients who underwent balloon mitralvalvotomy using Accura balloon, Karur et al. (20) observed procedural success in 95% of former to 100% in later. Similarly Harikrishnan et al. (21) compared 33 age and sex matched patients of less than 20 years using percutaneous mitral metallic commissurotomy (PMMC) with those using Inoue balloon mitral commissurotomy (IBMC). Similar success was seen in both groups of patients, 31 vs. 33 on both acute and three year follow up period with comparable hemodynamic parameters and restenosis rates. Both IBMC and PMMC are successful in providing relief from severe JMS in terms of gain in MVA and reduction in transmitral gradient.

The immediate results of PTMC in young were better than in adults .Procedure complications were not encountered in the young. This is most likely related to the more favourable anatomy in the young as demonstrated by a lower echocardiographic score (6).

Compared with Western countries, PTMC candidates from non-Western countries are younger, with more severe valve stenosis. However, PTMC achieves good immediate results in a similarly high proportion of patients, showing the wide applicability of this technique (22).

In our study only one patient required emergency Mitral valve replacement due to severe MR. In an Indian Study, 1.5% had severe MR warranting emergency mitral valve replacement (18).

Our study has certain limitations. Being a retrospective study, it is based on hospital database, so we could not comment on pre and post procedural clinical status of the patient. Further, change in pulmonary artery pressure, trans-mitral gradient, procedure success in relation to Wilkins’s score and follow up study could not be included in the study. Hence, further studies regarding prospective study and follow up are recommended.

In the developing country like Nepal our focus should be on primary and secondary prevention through screening. Systematic screening with echocardiography, as compared with clinical screening, reveals a much higher prevalence of RHD. Since RHD frequently has devastating clinical consequences and secondary prevention may be effective after accurate identification of early cases, these results have important public health implications (23).

Conclusions

Our study shows an excellent outcome of PTMC in term of safety and efficacy in JMS patients when performed in experienced centre by experienced operators.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Marijon E, Mirabel M, Celermajer DS, et al. Rheumatic heart disease. Lancet 2012;379:953-64. [PubMed]

- Roy SB, Bhatia ML, Lazaro EJ, et al. Juvenile mitral stenosis in India. Lancet 1963;2:1193-5. [PubMed]

- Reale A, Colella C, Bruno AM. Mitral stenosis in childhood: clinical and therapeutic aspects. Am Heart J 1963;66:15-28. [PubMed]

- Bhayana JN, Khanna SK, Gupta BK, et al. Mitral stenosis in the young in developing countries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1974;68:126-30. [PubMed]

- Shrivastava S, Tandon R. Severity of rheumatic mitral stenosis in children. Int J Cardiol 1991;30:163-7. [PubMed]

- Gamra H, Betbout F, Ben Hamda K, et al. Balloon mitral commissurotomy in juvenile rheumatic mitral stenosis: a ten-year clinical and echocardiographic actuarial results. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1349-56. [PubMed]

- Ben Farhat M, Ayari M, Maatouk F, et al. Pecutaneous balloon versus surgical closed and open mitral commissurotomy: seven-year follow-up results of a randomised trial. Circulation 1998;97:245-50. [PubMed]

- Reyes VP, Raju BS, Wynne J, et al. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty compared with open surgical commissurotomy for mitral stenosis. N Engl J Med 1994;331:961-7. [PubMed]

- Shrestha M, Adhikari CM, Shakya U, et al. Percutaneous Transluminal Mitral Commissurotomy in Nepalese children with Rheumatic Mitral Stenosis. Nepalese Heart J 2013;10:23-6.

- Adhikari CM, Malla R, Rajbhandari R, et al. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy in elderly mitral stenosis patients. A retrospective study at shahid gangalal national heart centre, bansbari, kathmandu, Nepal. Maedica (Buchar) 2013;8:333-7. [PubMed]

- Shrestha N, Dev Bhatta YK, Maskey A, et al. Immediate Outcome of Percutaneous Balloon Mitral Valvotomy in Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Bansbari, Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepalese Heart J 2015;12:11-4.

- Regmi SR, Maskey A, Dubey L, et al. Balloon Mitral Valvuloplasty (BMV) in pregnancy: A four year experience at Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre (SGNHC), Nepalese. Nepalese Heart J 2009;6:35-8.

- Rajbhandari R, Kc MB, Bhatta Y, et al. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy. Nepal Med Coll J 2006;8:182-4. [PubMed]

- Wood P. An appreciation of mitral stenosis. I. Clinical features. Br Med J 1954;1:1051-63. contd. [PubMed]

- Rowe JC, Bland EF, Sprague HB, et al. The course of mitral stenosis without surgery: ten- and twenty-year perspectives. Ann Intern Med 1960;52:741-9. [PubMed]

- Selzer A, Cohn KE. Natural history of mitral stenosis: a review. Circulation 1972;45:878-90. [PubMed]

- Yonga GO, Bonhoeffer P. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy in juvenile mitral stenosis. East Afr Med J 2003;80:172-4. [PubMed]

- Arunprasath P, Gobu P, Santhosh S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Baloon Mitral Valvotomy in Juvenile Rheumatic Mitral Stenosis. JACC 2014;63:S36.

- Sinha N, Kapoor A, Kumar AS, et al. Immediate and follow up results of Inoue balloon mitral valvotomy in juvenile rheumatic mitral stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis 1997;6:599-603. [PubMed]

- Karur S, Veerappa V, Nanjappa MC, et al. Balloon mitral valvotomy in juvenile mitral stenosis:comparision of immediate results with adults. Heart Lung Circ 2014;23:1165-8. [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan S, Nair K, Tharakan JM, et al. Percutaneous transmitral commissurotomy in juvenile mitral stenosis--comparison of long term results of Inoue balloon technique and metallic commissurotomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2006;67:453-9. [PubMed]

- Marijon E, Iung B, Mocumbi AO, et al. What are the differences in presentation of candidates for percutaneous mitral commissurotomy across the world and do they influence the results of the procedure? Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2008;101:611-7. [PubMed]

- Marijon E, Ou P, Celermajer DS, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease detected by echocardiographic screening. N Engl J Med 2007;357:470-6. [PubMed]